HDR from one Exposure

A challenge

Not long ago, someone handed me a severely underexposed raw image. The photographed scene depicted a building against a twilight sky. Presumably the exposure was metered on the sky; the backlight made the building almost black. The image came with a challenge: using your Photoshop skills, what’s the best you can you make from this original?

The image I got was very similar to what you see in figure 1. Thinking about how to proceed, I imagined there were two possible approaches:

- Keep the building black, as a silhouette, and give the sky a dramatic look

- Retrieve the detail that’s probably hidden in the darks, while retaining the beauty of the sky

Figure 1. Original image to be processed

The second option would result in what’s usually called an HDR-look. This has a somewhat bad reputation (think excessive detail and color) but if done with proper modesty, it can be an effective way of accurately reproducing a scene just how a human observer would have seen it. For sure, no one present would perceive the building of figure 1 completely black. We see detail in both the foreground and the sky. Even though a silhouette foreground is a nice photographic element, there is a strong case as well to recover the detail of the building. So I chose option 2.

(An additional argument for option 2 is of course that it provides a better showcase for my Photoshop skills.)

While working on the image, I hit a stumbling block that took me quite some time to overcome. The solution I found is the subject of this article.

Note: If you are not interested in the origin of the tutorial, skip to the paragraph called "The magic mask" below.

Gathering the two versions

Everyone would agree that the image is strictly divided in a dark “foreground” – the building, surrounding areas and some distant trees – and a light “background” – the sky. Our task is to bring detail into the foreground, keep detail and color in the sky, without arriving at an image that looks unnatural. That may be a challenge indeed, but why not go for it.

The strategy is to open two differently processed versions of the raw file – one for the sky and another for everything else – and blend them together using a suitable mask. So we start Photoshop, open the raw file, and see a default representation of our image shown in the Camera Raw plugin. There is not much to do for version 1: maybe some white balance correction or a straightening of some kind. Make sure the light areas do not contain blown-out areas. (If they do, correct this by moving the Highlights slider to the left.) Click Open and version 1 presents itself in Photoshop. This is very similar to figure 1 above.

Now open the same image for the second time. Camera Raw will pop up again for further processing. Undo any Highlight correction that was done for version 1. Now move the Exposure slider to the right: foreground detail is becoming visible. Keep moving until the building has gotten the look that you are aiming for. No more (or minimal) blacks, and detailing and natural color everywhere. The sky is lost, but don’t worry about that. Don’t be surprised if the Exposure slider has arrived at +3 or +4 stops. Figure 2 shows what we have now.

Figure 2. Same image, exposure pulled up to reveal shadow detail

If you never worked with raw files before, this result may astonish you. Despite the severe underexposure of the original, all shadow detail comes out when you ask for it. The only drawback of our vigorous move is… noise.

The latest Camera Raw contains a very handy new button called Denoise… The explanatory text tells us “Reduce noise with AI.” For now, I don’t care what that means, I just click that button and get a smooth and noise-free result without losing a lot of detail. Amount 50 will do for this image – in some cases less is enough or more is required. And of course, employ your favorite noise reduction software instead if you prefer that.

That’s it for our second version. Click Open and see version 2 available for editing in Photoshop.

The merge process: some futile efforts

We are nearing the hard part of the tutorial. After the foregoing, we have two files open in Photoshop: a dark and a light version of the same original. Now click the dark one (version 1), ctrl-A to select all and ctrl-C to copy that selection. Then, switch to the light one (version 2) and ctrl-V to put the copy as a second layer on top of it. The rest of the work is done on this two-layered file. The task is to find a mask that will reveal the foreground of the lower layer while keeping the sky of the top layer.

Well, that can’t be difficult, can it?

The usual instruction is: create a mask on the top layer and copy the image itself into it. I did exactly that (precise steps not relevant for now) and got a result with an acceptable foreground but a terribly flat sky: see figure 3. There is too much detail in the sky part of the mask, causing the texture in the real image to be wiped out. We need the mask to be white or very light where the sky resides.

Figure 3. First attempt. Note the boring sky.

All right, second attempt. Take the mask that we already have and apply the light layer to it in Overlay.

The idea is that the sky area will turn white in the mask, giving the sky its texture back. Figure 4 left is the result. Some of the sky has improved, but the darker clouds top right have deteriorated. And worse even, a nasty white halo has appeared on the edge between the trees and the sky (see figure 4 right).

Figure 4. Left: second attempt. Right: detail of the transition area

Third attempt. Remember that the Overlay blend mode is not commutative. A over B in Overlay gives a different result than B over A. So there we go: restart with a white mask on the top layer, apply the Background layer into it and then the top layer into that in Overlay mode. This gives a better result (figure 5 left). But I’m still not happy. Again look at the distant trees in the detail shown in figure 5 right: they don’t look natural do they?

Figure 5. Left: third attempt. Right: detail of the transition area

Here is a different thought. The current versions of Photoshop and Lightroom are good enough to create intelligent masks, right? So here is my fourth attempt. Start over again with a white mask. Go to the menu and Select – Sky. Convert this selection into the mask and… no, same trouble: a strong white line where the two parts intersect. Also the sky mask mostly forgets the sky that peeps through the big windows in the middle of the building. See figure 6.

Figure 6. Left: fourth attempt. Right: detail of the transition area

Rest assured that combinations of the above never yielded a satisfactory result. I started experimenting, using all sorts of different techniques, arrived at a method that looked promising, tested it on a myriad of comparable images (underexposed but with a HDR-like scene), did some fine-tuning, tested again, and finally came to a procedure that I think works in a large majority of cases.

The magic mask

Note: here the real tutorial begins!

Starting point is a two-layered file, where:

- the bottom layer is a light version of an image. It contains good detail in the shadow areas, while highlights can be blown out (example: figure 2 above)

- the top layer is a dark version of the same image. It contain good detail in the highlight areas, while shadows can be blown out (example: figure 1 above)

For clearness, I renamed my layers to Foreground details and Sky details resp. See figure 7 for the layer stack right before starting the procedure.

Figure 7. Layer stack to start from

1. Click on the top layer in the Layers panel and add a layer mask to it. With the focus at the new mask, from the menu: Image – Apply Image… On the popup that appears, enter Source Layer: Foreground details (the bottom layer) and Blending: Normal. (See figure 8.) Click OK.

Figure 8. Apply Image for step 1

2. With focus still on the mask, Menu: Filter – Blur – Gaussian Blur. Enter a very high number, e.g. somewhere between 100 and 500 pixels. If there is a clear distinction between the light and dark areas, the number must be closer to 500. Otherwise, a lower number is also good. For the current image, I choose 400.

3. Next, open the Channels panel and click the + icon on the bottom bar to create a new channel. Give it an appropriate name if you prefer that. On this channel, Menu: Image – Apply Image… and enter Source Layer: Foreground details, Channel: RGB and Blending: Normal. (This looks just like figure 8, except that the target is not the layer mask but the channel we just created.) Hit OK.

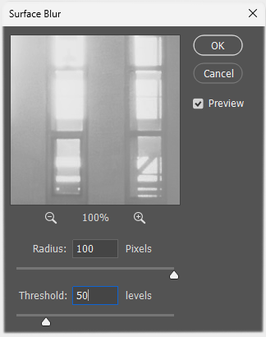

4. Still on the same channel, go to Menu: Filter – Blur – Surface Blur and enter Radius 100 and Threshold 50. (See figure 9.) Hit OK.

Figure 9. Surface Blur for step 4

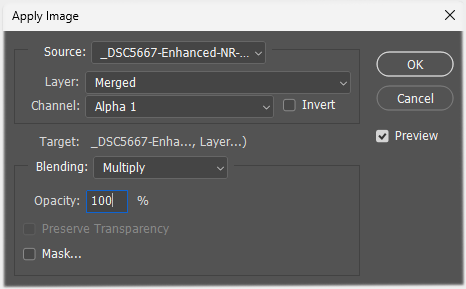

Figure 10. Apply Image for step 5

5. In the Channels panel, click the RGB to reset the focus to the image itself. Click the layer mask of the Sky details (top) layer and Menu: Image – Apply Image… Enter Channel: the channel you just created and Blending: Multiply. (See figure 10 - my channel name is just "Alpha 1".) Hit OK.

6. With the focus still on the layer mask, Menu: Filter - Blur - Gaussian Blur and enter Amount 2.This is a step that in some cases improves the look of the edges, especially where these contain fine detail.

That’s it! Figure 11 shows the mask we just created and figure 12 is the final result. Good detail in both foreground and sky, and no artifacts in the areas where the two meet. See figure 13 for the result around the transition between foreground and sky.

Figure 11. Final mask

Figure 12. Final result

Figure 13. Detail from figure 12.

What remains to be explained is a few optional steps that may apply if you don't like the result so far.

The optional steps 1: Reduce the HDR effect

The image of figure 12 has a typical HDR look. One could judge the foreground too light to be natural, given the colorful and detailed sky, leading to rejection of the end result. But before you throw the method in the trash can, consider the following two quick fine-tuning methods:

- If you find the foreground too light, double click the layer mask of the top layer and move the Density slider to any value lower than 100.

- If you find the sky too dark, change Opacity of the top layer to a value lower than 100.

- If you find both, do both.

Figure 14 is the result of setting both the mask density and the layer opacity to 70.

Figure 14. Reduced HDR effect to 70%

The optional steps 2: Increase the HDR effect

What if you want an even stronger HDR effect? This is less obvious, but a possible technique is the following: apply the layer mask of the top layer to itself in Overlay mode. The expected result is a darker sky and a lighter foreground. Be aware that this idea hasn’t been extensively tested, and some of the test images gave an inferior result – so proceed at your own risk. Beware in particular of artifacts around the edges between lights and darks.

An alternative that always works is of course to redo the raw processing and start with lighter c.q. darker layers.

The optional steps 3: Restore color

You may have noticed that just above the horizon and around the building in figure 12, some color has been lost. This is a consequence of the action’s mechanisms. Here is a possible way to correct this shortcoming.

- Create a new channel and apply the top layer into it in Normal mode.

- Apply the bottom layer to the new channel in Overlay mode. This makes the channel mostly dark in the foreground areas, and mostly white in the sky areas. See figure 15.

- On top of the layer stack, add copies of the bottom and top layer. The resulting stack has 4 layers.

- Set the two new layers to blend mode Color.

- Add a layer mask to the copy of the bottom layer and apply the new channel to it, inverted.

- Apply the new channel to the new top layer in Normal mode (not inverted).

Figure 15. Mask for the "Restore color" steps

Figure 16. Final result after applying the "Restore color" steps

That’s it! Make group of the top three or four layers, and call them HDR group or something like that. Or make a group of the top two layers and call them e.g. HDR color group.

Figure 16 shows the result with the new color layers. Note the better color in the sky, especially above the horizon. There may be cases where this color restoration has no perceptible effect, but it will never harm the image.

Some final remarks and a downloadable action

- The example above started with a severely underexposed image, but this is certainly no requirement for the procedure to give good results. Start with a normally exposed raw image, create one version that exhibits the shadows and another the highlights, and off you go. It must be a raw image to start with though.

- Of course fine HDR images can be created from multiple exposures of the same scene. Admittedly, this will give a better results in terms of detail and noise, but using multiple exposures has its drawbacks too, like moving objects. Working with a single original never has that problem. And don’t forget, the procedure as given above may give a perfect result when applied to two different exposures! Except of course… it doesn't include deghosting support.

- The action will only give an acceptable result if the dynamic range of the photographed scene is too high for one exposure. Otherwise, the procedure still works but won't do much more than make the image very flat.

(But hey, isn’t that the whole point of HDR photography?)

As you might have expected, I have made a Photoshop action available for download which executes all above steps automatically. It will perform the steps as listed in the paragraph "The magic mask" above plus the steps as listed in the paragraph "The optional steps 3: Restore color". The result is a three-layered group that will get the descriptive name HDR Group.

You can find the action together with a concise manual on the Downloadable actions page. Feel free to use it.

Gerald Bakker, 31 Oct. 2024

Tutorials and Actions